Emily Bell

Director, Strategic Communications, Net Zero Infrastructure Lead

What are you looking for?

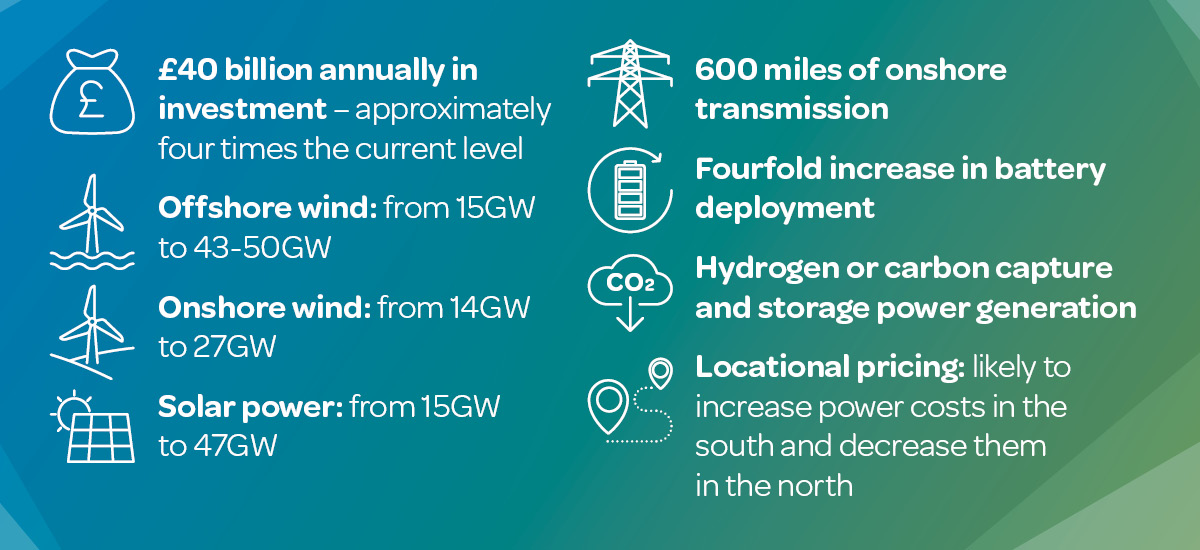

NESO outlines two pathways to achieving clean power by 2030, each balancing clean dispatchable power and renewables, but both require substantial increases in various areas:

Beyond financial investment, a reformed planning and consenting system is crucial. This includes standardising and digitising data to foster innovation and new market entrants, increasing the skilled workforce, expanding energy storage, and creating a more flexible and responsive energy demand system.

NESO concludes that achieving these goals by 2030 is feasible without significantly raising energy bills, but it requires perfect execution. Both the Government and the industry must work together to make this vision a reality.

For a more detailed summary, and our views on NESO’s advice, please see the sections below on infrastructure, planning/consenting and markets/flexibility.

The clean power mission must be about delivery. The headline investment required is about £40 billion a year, about four times the current run rate. That is a good rough multiple of what we need to do across all sectors; offshore wind, solar, onshore wind, the transmission network. There are also those first-of-a-kinds, such as gas power with carbon capture or clean hydrogen power generation. It isn’t just to meet the electricity demand of today, the advice expects there to be an increase of around 20% in electricity demand and 10% in peak power by 2030. Some of that will be quite concentrated due to major industrial decarbonisation schemes such as Tata steelworks in Port Talbot.

The core of the system will be offshore wind, with a need for around 30GWs more by 2030 (there is only 15GW today). Although that is extraordinary growth, the advice is that there are enough projects in the queue to meet this, but much of that is still preliminary and NESO use the word “challenging” to describe its delivery by 2030. When considering we are looking at a delivery of around 10GWs a year against a run rate of <2GWs, you get a feel for the scale of this. The word “challenge(s)” is used 63 times in the document.

Onshore wind will need to about double in capacity from 14GW to 27GW by 2030. Here, it feels more approachable, with around 3GWs a year needed, figures we have approached in the past. The removal of the de-facto ban on onshore wind in England is the first step in facilitating growth in this sector, which to date has been focused particularly on Scotland, as well as Wales. Still, that is around 130 of the proposed Scout Moor wind farm which will be the biggest wind farm in England to date.

Solar is suggested to go from 15-47GW by 2030. Although this is a huge increase, the solar industry is famously flexible and in a global supply chain of >500GWs a year and growing, this feels like something that can be done, the challenge is more around connecting it to the grid (see below).

Most other forms of generation are deemed unlikely to be able to provide much more capacity by 2030 and in the case of nuclear, the capacity declines. Gas CCS and hydrogen projects are projected to play a significant role post-2030, but <3% by 2030 and there is great uncertainty about costs. Small modular reactors, tidal and biomethane are deemed too uncertain to allocate any role in 2030.

The advice explains that although unabated gas generation must account for <5% of total, the big troughs of energy supply that there will be with a wind dominated system will mean most of current power stations will still be needed, albeit running for much fewer hours. How we do that cost-effectively is a major question.

All this new generation needs to be connected up and the advice refers to the Pathway to 2030 report which identifies 600 miles onshore and 3,000 miles of additional offshore networks in order to deliver the power to the point of demand. NESO seem at home here, with a clear existing plan and much of the specifics in place, albeit with much of it requiring acceleration. They emphasise the need to accelerate development consent orders and changes to the Town and Country Planning Act. The importance of the additional network is illustrated in the scale of constraint payments paid to generation that can’t be transmitted; as much as £12.7 billion per year.

As well as the transmission connected generation, distribution network operators indicated there is 2-3 times the amount of renewable energy in their queues that is required for 2030!

What is more incredible is that there are already more projects in the connection queue in every sector than are projected to be needed by 2030 (please refer to the graph on page 40 of the report). There is a lot of sorting and pruning to do.

As NESO sets out in their report, most of the energy infrastructure required to deliver clean power by 2030 is already in the development cycle – the majority of which is at the early design and pre-consenting stage. This means that a significant volume of applications for planning permission will need to be submitted in the short term to provide the relevant approvals to deliver this vital net zero infrastructure.

It is widely recognised that the existing planning and consenting system is not fast or efficient enough and will need improving and accelerating if it is to enable the rapid deployment required. The response cites an average 21 months for a planning decision on offshore wind in England and 15 months in Scotland. Longer timeframes are quoted by NESO for onshore wind, which relate to projects in Scotland and Wales (with no recent applications in England). These timescales are significantly constraining to the overall programme for delivery which requires schemes to have started construction within the next 6 -24 months.

The engagement undertaken by NESO found the main issues affecting planning timescales are societal acceptance, local community resistance, local authority planning resources and statutory consultee resources and collaboration, as well as ensuring the right data is available.

This emphasis on reform of the planning process to speed up projects, but recognition of the need to improve community engagement is not necessarily contradictory, but requires resources, clarity and a balance of priorities. NESO places this squarely at the feet of the Government to deliver. There is recognition of the need for transparency within the industry, which must be the same approach taken when we look more widely if we are to meaningfully combat misinformation, misunderstanding and resistance at a community level. Openness in proactive and accessible communication will be key to achieving the pace that is so critical.

“With a short and shrinking window of time, pace must be the primary goal. However, this cannot come at the expense of public consent or excessive cost as that would mean the clean power objective would be self-defeating.”[1]

NESO has also published their proposed connections reform. In simple terms, this will move to prioritise projects that are ready to go, and with planning permission, rather than the old model of first come first served. There is also a move to consider alignment with the strategic plan allocation for where NESO proposes projects to be delivered. This is unlikely to be an issue early on as so much is required, but, in time, it may lead to projects being refused on the basis that they don’t match the spatial plan, even if otherwise viable.

Reform of energy markets may seem like the least consequential as it doesn’t directly involve building anything, but it is crucial, and its impact fundamental, in a wind dominated energy system. As the clichéd question goes, “what are we going to do when the sun isn’t shining and wind isn’t blowing?” The answer from NESO, is a hierarchy of:

Firstly, it is crucial that business and households are incentivised to be flexible in their energy use to help balance supply and demand with all of this new wind and solar generation. Homes will play a growing role in the future, especially as we all get electric vehicles and switch to heat pumps. The public will need to be responsive when they charge (and discharge) cars and heat hot water tanks, but currently most of us pay the same for electricity whenever we use it; that will need to change and innovative tariffs and automation will be needed, as will an appropriate and responsive regulatory system.

That blends into the use of batteries. There are already a lot of static batteries providing a variety of services to the grid and we will need a lot more, projected to go from 5GW to around 25GW. Vehicles are a huge opportunity that is barely being touched. By 2030 there will be tens of GWhs of batteries on wheels. As well as reducing charging at peak demand times they can feed energy in, vehicle-to-grid.

Finally, the unabated gas, described above.

The analysis suggests that more long duration energy storage, such as pumped hydro and novel technologies such as liquid air, long duration batteries, etc. have a role to play but need to be mobilised fast. The challenge with the deployments is that they are likely to be expensive as they are first of a kind or have not been deployed for a long time, and some with their own planning and environmental challenges.

There is clear support for locational pricing which will please some and worry others. The principle is that by contracting for energy generation at the same price we are encouraging generation to ignore the costs it imposes in transmission. The poster example of this is getting wind power from Scotland, which has loads of generation, to southern Britain which has more demand. In simple terms, locational pricing will make energy cheaper in some parts and more expensive in others; we are likely to see more wind farms in the south and more data centres in the north. This can reduce the need for network upgrades, but it makes project finance more complicated and may delay projects already planned, just when we need to accelerate. This increases the pressure on the Government’s decision on the Review of Energy Market Arrangements (REMA), where this is addressed.

Positively, there is a sense that digitalisation and enabling innovative services to enter the market can deliver much greater demand flexibility and little cost. We have long been making the case for how smarter analysis and better data can reduce the size of grid connections needed, reduce energy bills and enable decarbonisation. NESO’s point that getting this right requires collaboration between them, Government, OFGEM and Elexon illustrates why it has been slow to come. The assumption that by 2028 time-of-use tariffs are the default option, shows how fast they expect us, as the public, to change.

The quadrupling of investment outlined applies across all elements of the electricity energy system. The investment of £40 billion a year is equivalent to the tax rises announced in the recent budget and >1% of the UK GDP.

There are some parts of the plan that you can see could be as flexible as needed without creating a supply chain crash; the solar market is so big and responsive that it could absorb our growth, but other elements are already under strain. The previous Government commissioned a report published in April that highlighted high supply chain risk for offshore wind vessels, transformers and switchgear, HVDC cables and floating wind foundations.

That is just the manufacturing side, there are also increased needs for engineers, planners and lawyers, investors, acoustic consultants, etc. For example, the advice cites an Offshore Wind Industry Council report that suggests we need to treble the number of skilled people in offshore wind alone to 100,000. This feels like a massive problem as skilled people take years to develop. There is a hint at increased immigration in specialist areas. Similarly, there is a request for long-term policy certainty and line of sight for funding, but by its nature this takes time to take effect. There are opportunities at development and project level to consider meaningful social value opportunities – communicating and engaging with the younger generation to build understanding for emerging job opportunities and the role they could play in the transition to net zero.

One area that may be ease the challenge across the board lies around increased digitisation and the use of AI to simplify and speed up processes. NESO acknowledges that legacy systems and protocols have not allowed them to make the most of new technologies but are confident a digital-first mindset can do better and enable innovation for them and our sector as a whole. You sense in their engagement that the industry is itching to use data and tools to drive innovation, but needs that common platform, markets and data sharing to be able to do it.

If successful, NESO point out that this turbocharged transition will create jobs, enable electrification of demands and sectors dependent on clean power and reduce energy price volatility. It may also give opportunities for industry to export its skills and goods to a global market following in our path.

The big claim we are seeing in the press is that all this can be done without increasing energy bills. This is based on consumers accepting an imposed carbon price on fossil fuels, however, these things are policy options not natural costs; effectively pricing in externalities. The numbers are also predicated on the assumption that this rapid ramp-up in delivery won’t cause price prises in less flexible parts of the supply chain and the advice acknowledges that is a big risk.

The good news for the Government is that NESO has sketched out a pathway to their 2030 goal and identifies environmental benefits and the opportunity to unlock some economic opportunities. The challenge is that it is left for Government and those in the industry to deliver it and we have no time to waste.

We understand the urgency and work with our clients to shape a more sustainable future. We work across all areas of net zero infrastructure and engage with all relevant consenting regimes. For more information, please get in touch with a member of the team or download our brochure.

13 November 2024

[1] Clean Power 2030

Director, Strategic Communications, Net Zero Infrastructure Lead

16 September 2024

We have recruited Nicola Riley as Senior Director in our Net Zero Infrastructure team.