Comment

The revised standard method – are we nearly there yet?

Our Chief Executive, Dave Trimingham, considers the implications of the revised standard method and whether we are making progress.

Over last weekend I poured a large glass of red and digested Chris Young QC’s tour de force on the proposals for revising the standard method (SM) for assessing housing needs. Here I add a few personal thoughts on the journey towards a way of delivering the right amount and type of housing across England.

My first observation is that Government has listened:

The proposed SM now starts with the end in mind. The end in this case is the delivery, on the ground, of 300,000 new homes a year. The proposal accepts that we have to start by planning for significantly more than that (337,000 as proposed) to allow for “slippage” between what is planned and what is built.

The move to a starting point for assessing housing need that includes a baseline which uses the current housing stock of an area is also hugely positive. Underlying drivers of the need for more homes include factors such as birth rates, longevity and changing household circumstances. Give or take, these don’t vary wildly across the country. Using stock rather than household projections removes from the equation factors such as the effects of economic cycles, the availability of housing, and its price (which in many ways have contributed to the housing crisis). It is in short a truer reflection of actual need, and where it is likely to originate. It has the added advantage of being more stable and predictable as a basis for plan-making.

So that is several steps in the right direction. But it could be better still.

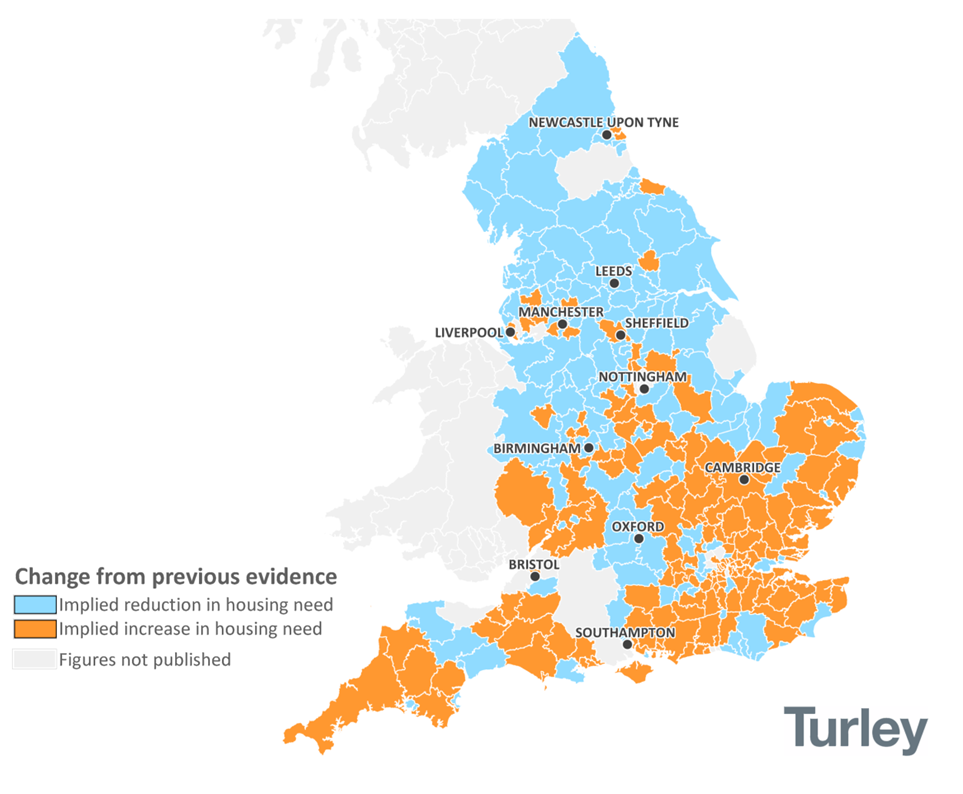

When a review of the SM was first mooted by Government it was at least partly in response to concerns about the national distribution. The current SM produces figures well above what has previously been planned for in some areas and, perversely, figures below what was being planned for in others. There was a notable South-North divide (see Figure 1).

A renewed focus on the socio-economic disparities between different parts of the country saw the Government promising “levelling up”, and it won a resounding election victory. Many therefore hoped the revised SM would deliver something more achievable and equitable in all regions.

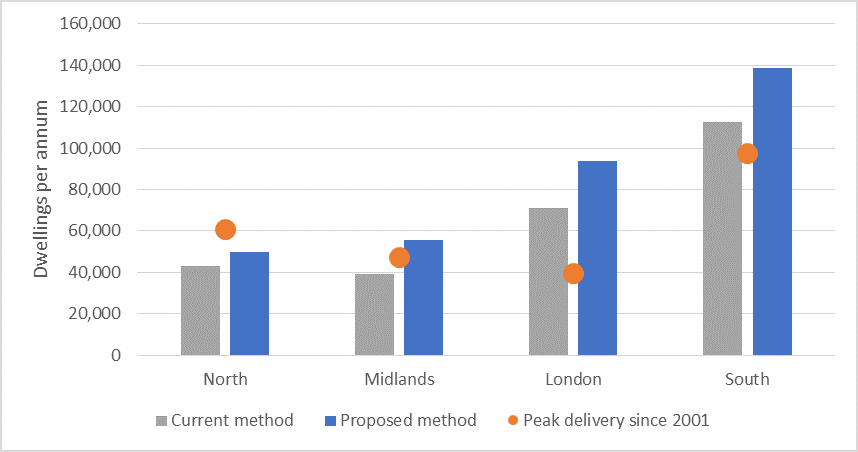

And yet the implications of what was published on 6 August are illustrated in Figure 2 and include:

- A further 31% uplift from the current method in London – to a figure nearly two-and-a-half times the highest delivery in the past 20 years. Is such an increase deliverable in the short term given that the London Plan proposes much lower requirements?

- 26% more homes across the South [1] - around 73% higher than recent best delivery. Concerns about the capacity to achieve this are being voiced by a growing number of Local Authorities and backbench MPs

- But only 15% more across the North [2] - still a puzzling 17% below current delivery. Is that responding to real needs?

In short the upshot is figures so high in London and the South as to make their deliverability - at least in the short term - highly questionable; and figures in the North that imply a lack of ambition, and a disconnect with actual housing needs that will frustrate rather than enable levelling up.

Perhaps the most stark illustration of this is that while the consultation makes clear that housing should respond to market signals - such as demand - it proposes 20% lower figures in the North than were delivered last year [3]. There is no clearer market signal than homes completed and delivered.

So why has this happened? And, more to the point, how can it be rectified?

The cause is twofold:

- Using only 0.5% of the current housing stock of an area in establishing a baseline (step 1 of the revised SM) downplays the underlying drivers of housing need. It would by itself suggest a national need for just 122,000 homes – just 40% of the 300,000 target.

- From this low base, and in order to get to a meaningful national target, the proposed adjustment to address affordability over-emphasises price as a measure of housing demand – and perhaps the effect that increasing supply can have on affordability.

So there is no doubt - it is absolutely right, in my view, that more housing should be focussed on areas where it is least affordable. The UK has some of the highest housing prices and simple economics says if supply increases price will fall.

But that will only take us so far. It has to be recognised that affordability is not the only indicator of where homes are needed. This is illustrated in locations where affordability is relatively low but large numbers of new homes are still built and occupied. Where needs are qualitative not just quantitative. Or where the needs of those who can’t access the housing market go unmet.

If the crisis is to be addressed land has to be available to meet that supply. In the case of some boroughs, mainly in the South of England, that means doubling or tripling the amount of land that must be found. Land that is suitable and available for housing is in short supply. It is in demand for many uses (or none) besides housing. The reality is that in some parts of the country there isn’t enough land to deliver the scale of increase in supply that would be needed to meaningfully moderate the cost of homes.

So increase in supply is part of the answer but a national solution to the housing crisis has to also address the demand side.

“Levelling up” is, at its core, about influencing demand. About stimulating and creating opportunities in all parts of the country. Housing has a vital role to play.

The Government’s commitments to invest in the economies, high streets and infrastructure of the regions is fundamentally about spreading demand in the economy beyond the current gravitational pull of London and the South East. Housing is integral to this.

And now is surely the time for Government to be positive in doing this.

It is both the jobs that the economy creates and the need to travel in order to perform them that has created hotspots of overheating in the housing market. These factors have increased exponentially demand for homes in “commutable” locations.

But, lockdown has loosened the connection between where we work and where we live – in my view forever. The prospect (attractive to many) of a “hybrid” model of mixed remote and workplace working fundamentally changes the requirements of where we live. The demand for housing is more geographically flexible now than it has been in my lifetime. Research by the HBF [4] reveals a recent surge in demand for new homes as people review their locational needs and adapt to the prospect of more home-working.

Add to this what lockdown has shown us about the contribution of outdoor space, exercise and time in nature to our wellbeing and the places we want to live are also changing. There is emerging evidence of growing demand for homes with gardens and access to good quality open space.

This combination of circumstances presents a once in a generation opportunity to rebalance our lives, our economy and our country. (Wow. How did I get here when I started talking about the Standard Method?!).

So can the SM address this?

Well, not by itself, of course. But with some achievable tweaks it could take a major step in the right direction.

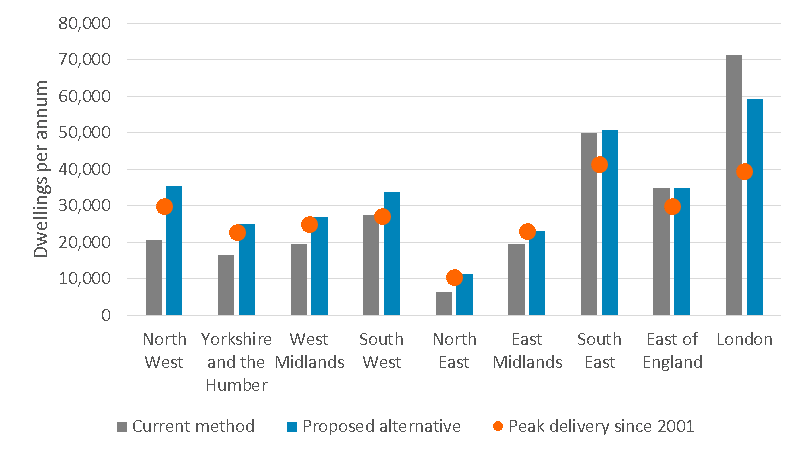

Using say 0.7% or 0.8% (rather than 0.5%) of existing housing stock in the baseline (step 1) would be a better reflection of real housing needs in all locations across the country. In combination with a moderation of the adjustments for affordability (step 3) to avoid undeliverable targets in certain hotspots, this would make a transformational difference to the national distribution of housing. These “tweaks” would maintain the focus on increasing supply in the areas where housing is least affordable – a critical policy objective – while broadening the range and choice of housing, and the boost to construction and jobs that follows, across the whole country.

A national picture might look something like this:

It is important that tweaks to the SM are carried forward now (and Government avoids the temptation to postpone change until a new Local Plan system, as sketched out in the White Paper, can take the strain). This is because:

- They address the main shortcomings of the current SM – a higher national figure with a spread that is ambitious but deliverable in all regions;

- They can play an important part in economic recovery from the effects of the pandemic – housebuilding is a huge employer and contributor to the national economy – both directly and through supply chain and spin-off effects. Ensuring all parts of the industry can optimise their capacity can help drive economic growth; and

- They would be a foundation for the Government’s broader ambitions for levelling up – demonstrating a clear and firm commitment on which reforms planned through the impending Devolution White Paper, reforms of the plan-making system, and investment in physical and digital infrastructure can build.

So, in my view, we are nearing our destination with a little careful work still to do.

15 September 2020

[1] East of England, South East and South West Regions including London

[2] North West, North East and Yorkshire & Humberside

[3] The North East, North West and Yorshire and Humber delivered a combined 60,000 new homes compared to c. 50,000 proposed in the revised SM

[4] Demand for new build homes rockets post lockdown